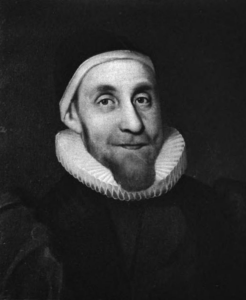

Today is the birthday of Robert Burton, who was born at Lindley in Leicestershire in 1577. In 1621, he published a very long and very strange book called ‘The Anatomy of Melancholy’. In it, he addresses the subject of melancholy; the causes of it and what he thinks we should do about it. Burton was himself, a sufferer from melancholy, what we would now call depression, and he tells us that: “I write of melancholy by being busy to avoid melancholy.”

Today is the birthday of Robert Burton, who was born at Lindley in Leicestershire in 1577. In 1621, he published a very long and very strange book called ‘The Anatomy of Melancholy’. In it, he addresses the subject of melancholy; the causes of it and what he thinks we should do about it. Burton was himself, a sufferer from melancholy, what we would now call depression, and he tells us that: “I write of melancholy by being busy to avoid melancholy.”

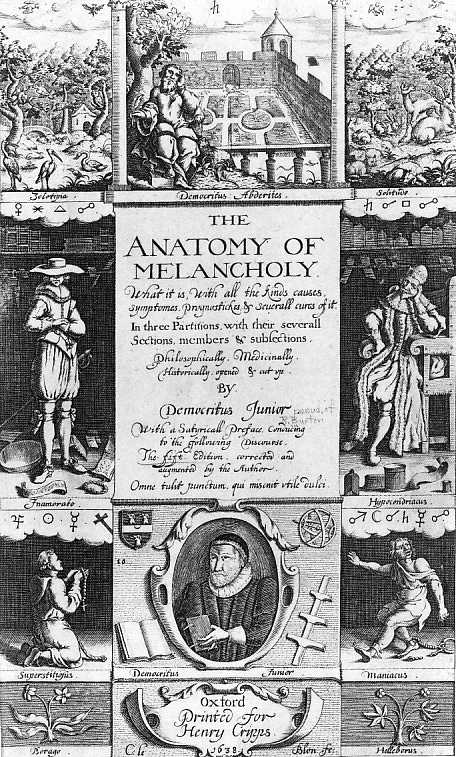

Burton studied at Oxford University and spent the greater part of his life there both working in the library and as the vicar of a local church. He was a voracious reader and his book is packed with references and quotes from works ranging from the classical literature of Greece and Rome, through the medieval period to the renaissance and up to, what were for him, the works of modern writers. In fact, using his subject of melancholy, he looks at all human emotion and thought and includes citations from just about every book available to a learned man in the seventeenth century. The Anatomy of Melancholy is a medical manual, it’s an encyclopaedia, it’s a mine of clever quotations, it’s a self-help book, it’s a mess. But lots of people love it. His first edition ran to nine hundred pages, but he revised it five times during his life and his last version, published shortly after his death, was two thousand pages. A lot of seventeenth century texts are a bit all over the place, but Burton’s book is a particularly fine example. It’s almost impossible to read from cover to cover, but it’s lovely to dip in and out of. The index is a joy in itself. A quick look will tell you that he has written about aerial devils, beef – a melancholy meat, why poets are poor and the urine of melancholy people.

Burton believed in the humoral system of medical diagnosis which had been outlined by Hippocrates, expanded on by Galen and had basically been around for about two thousand years. Here is how it works: the four humors; phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile are four liquids which flow around the body. Ideally, they are in perfect balance, but that is rarely the case. An excess of one or another leads to different personality traits. Phlegm, which is governed by water, makes a person ‘phlegmatic’ which is calm, thoughtful, patient and peaceful. Blood is governed by air, it makes people ‘sanguine’, they are courageous, hopeful, playful and carefree. Yellow bile is governed by fire and causes a person to become ambitious, leader-like, restless and quick to anger. Black bile is governed by earth and makes a person despondent, quiet, analytical and serious. If any of these humors are badly out of balance, they can cause disease, the symptoms can be both physical and psychological. Too much black bile is a cause of melancholia. In fact, the word comes from the Greek: melaina (black) and kholé (bile).

People believed that the quantity of these humors were affected by the food you ate, how much exercise you got, how much you slept, even the sort of air you were breathing. Treatments for symptoms were tailored according to the patient’s humoral temperament. There is no such thing as black bile, and they meant something completely different by the word phlegm from the way we understand it, but it was a system that had it’s good points. It meant that physical diseases could also have symptoms that were psychological and vice versa. So for Robert Burton, a psychosomatic illness was every bit as real as one with a physical cause. He knew that melancholia was a real illness and that telling a depressed person to cheer up was every bit as useless as telling an injured person to stop hurting or someone with a fever to stop being so hot.

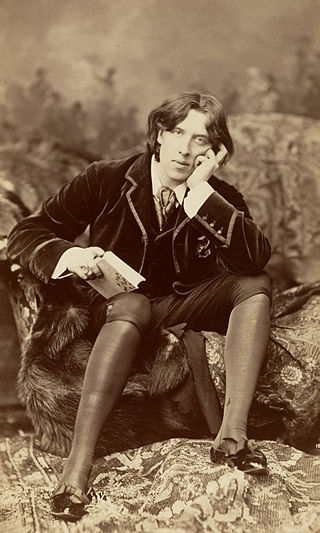

Melancholy was actually quite a fashionable thing to suffer from in the seventeenth century. Here’s why: Back in Ancient Greece someone, possibly Aristotle, mused about why it was that all the greatest artists, poets and philosophers were predisposed to melancholy. During the renaissance people rather took up this idea and ran with it. A melancholic disposition became a sign of a great artist or a sensitive soul. People started to have pictures painted of themselves mooning about under trees, perhaps wearing black. It became something that was considered attractive and generally associated with genius. (It is a look that hasn’t really gone away, take the photograph of Oscar Wilde taken some time in the 1880s.)

Melancholy was actually quite a fashionable thing to suffer from in the seventeenth century. Here’s why: Back in Ancient Greece someone, possibly Aristotle, mused about why it was that all the greatest artists, poets and philosophers were predisposed to melancholy. During the renaissance people rather took up this idea and ran with it. A melancholic disposition became a sign of a great artist or a sensitive soul. People started to have pictures painted of themselves mooning about under trees, perhaps wearing black. It became something that was considered attractive and generally associated with genius. (It is a look that hasn’t really gone away, take the photograph of Oscar Wilde taken some time in the 1880s.)

So Burton’s book was really rather popular. He does warn though, that although it might seem attractive at first, too much melancholia can lead to serious problems and you should really try to do something about it. Writing helped him with his melancholia, as did reading, but he was aware that reading is a solitary occupation that can lead to melancholia. Particularly, he cites too much learning as a source of sorrow, which is rather sad but probably true. In certain passages he will warn his reader that if they are suffering from a certain type of melancholia, they might not want to read the next bit. Or he says that if what they are reading is making them feel sad, the next bit might cheer them up a bit. Goodness, comic interludes and trigger warnings from the seventeenth century, I really like Robert Burton.

So Burton’s book was really rather popular. He does warn though, that although it might seem attractive at first, too much melancholia can lead to serious problems and you should really try to do something about it. Writing helped him with his melancholia, as did reading, but he was aware that reading is a solitary occupation that can lead to melancholia. Particularly, he cites too much learning as a source of sorrow, which is rather sad but probably true. In certain passages he will warn his reader that if they are suffering from a certain type of melancholia, they might not want to read the next bit. Or he says that if what they are reading is making them feel sad, the next bit might cheer them up a bit. Goodness, comic interludes and trigger warnings from the seventeenth century, I really like Robert Burton.

Lots of other people have enjoyed his book too. Some because they recognised the symptoms in themselves, Some have read it to find impressive quotes in Latin to make themselves look clever. The Anatomy of Melancholy was a favourite of dictionary compiler Samuel Johnson. Samuel suffered from bouts of depression and said the Burton’s book was the only book that ever took him out of bed two hours sooner than he wished to rise. Laurence Sterne borrowed his sprawling style with its extensive use of footnotes for his novel ‘Tristram Shandy’. He was rather making fun of Burton, but he also lifted a large section of text directly from The Anatomy, for which he got into trouble. The poet Keats loved the book and it was an inspiration for some of his poetry. Byron mined it for quotes to impress women with. His book has been also much admired by Samuel Beckett, Philip Pullman and Nick Cave.

It’s worth seeking out The Anatomy of Melancholy, even just for a glance through the index. His suggested cures are not really recommended. Most of his cures for sleeplessness involve opium, but he also suggests horse leeches behind the ears or smearing your teeth with earwax from a dog. He does describe the way people are often kept awake by worries in a rather lovely way though. He says it is called ‘being led around the heath by Puck’, which makes it sound a lot more fun than it actually is. Often he recommends just going along with whatever the patient says and just telling them that they can be easily cured. He has a story about a king who believed that his head had been cut off. He was cured by being given a leaden cap to wear, so that he could really feel it weighing on his shoulders. While having your head cut off is not really a fear many of us can relate to, for a king in days gone by, it could have been a very real worry. The way people’s symptoms manifested is both very different from our own but at the same time sometimes oddly familiar. Burton also describes ‘The Glass Delusion’, a surprisingly common belief that the patient was made from glass and might easily shatter. I wrote about this elsewhere back in the summer. If you think of it as a way a person suffering from anxiety might describe their feelings it’s completely understandable.

Brilliant, must try and find a copy, sounds like just what I need… Opium rather than ear wax for me though please xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

You can find it online for free at internet archive or project gutenberg. x

LikeLiked by 1 person