Today is the birthday of Lady Hester Stanhope. She was born in 1776, the eldest child of Charles, the 3rd Earl Stanhope, at Chevening in Kent. Hester was an adventurous traveller, deeply eccentric and self-styled Queen of the Desert. In her late twenties, she lived at Downing Street where she acted as hostess for her cousin, William Pitt the Younger, who was then Prime Minister. She acted as his secretary and sat at the head of his dinner table making witty and intelligent conversation. Hester was in her element, but it didn’t last. Pitt died in 1806 and she was left homeless, but with a tidy pension of £1200 a year from the government in recognition of her services.

Today is the birthday of Lady Hester Stanhope. She was born in 1776, the eldest child of Charles, the 3rd Earl Stanhope, at Chevening in Kent. Hester was an adventurous traveller, deeply eccentric and self-styled Queen of the Desert. In her late twenties, she lived at Downing Street where she acted as hostess for her cousin, William Pitt the Younger, who was then Prime Minister. She acted as his secretary and sat at the head of his dinner table making witty and intelligent conversation. Hester was in her element, but it didn’t last. Pitt died in 1806 and she was left homeless, but with a tidy pension of £1200 a year from the government in recognition of her services.

She lived for a time in Montagu Square in London and then moved to Wales. In 1810 she was advised by her doctor to make a trip to the Continent, for the sake of her health. She would never return. She travelled with her private physician and later biographer, Dr Charles Meryon. They stopped off in Gibraltar, where she picked up another travelling companion, a wealthy young Englishman called Michael Bruce. Although he was twelve years younger than her, they were soon lovers, much to the disappointment of Dr Meryon. From there, they travelled on to Malta, Greece and Constantinople. Here, she met with the French Ambassador. She had a mind to go to France and ingratiate herself with Emperor Napoleon. She thought if she could find out what made him tick, she could return to Britain with information that could lead to his overthrow. It was a mad plan and luckily the British government got wind of it and stopped her.

With nothing better to do, she and her swelling entourage decided to head for Egypt. On the way, they were shipwrecked off the island of Rhodes. Everyone lost their luggage and it led to Hester spending the night in a rat-infested windmill with a bunch of drunken sailors for company. Separated from her belongings, she had to find other clothes. Rather than wear a veil, she chose to dress in a robe, turban and slippers. When they eventually arrived in Egypt, she bought a purple velvet robe, embroidered trousers, a waistcoat, a jacket and a sabre. She found men’s clothes preferable and dressed that way from then on.

In Alexandria, she and her party set about learning Turkish and Arabic. The East was now in her blood and they pressed onwards to Lebanon and Syria. On the way, she met with many important Sheiks, some of whom would have been very dangerous enemies. They had never seen anything quite like her before and she seems to have been well received. Some accounts tell of how she was hailed as a princess, but it also seems possible that they all thought she was a bit mad and that just going along with her would be the polite thing to do. When she reached Damascus in 1812, she insisted on entering the city unveiled and on horseback, both of which were forbidden, but she seemed to get away with it.

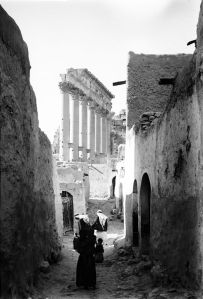

The following year, she visited the ruined desert city of Palmyra. It had once been ruled by Queen Zenobia who had led a revolt against the Roman Empire in the third century. No European woman had ever seen the city before. It was a week’s ride away from Damascus over a wasteland that was ruled by dangerous Bedouin tribes. She made the journey dressed as a Bedouin and took with her a caravan of twenty-two camels. The people of Palmyra were impressed by her courage and gave her a crown of palm leaves. She was a bit carried away by this and later wrote: “I have been crowned Queen of the Desert. I have nothing to fear…I am the sun, the stars, the pearl, the lion, the light from heaven.”

The following year, she visited the ruined desert city of Palmyra. It had once been ruled by Queen Zenobia who had led a revolt against the Roman Empire in the third century. No European woman had ever seen the city before. It was a week’s ride away from Damascus over a wasteland that was ruled by dangerous Bedouin tribes. She made the journey dressed as a Bedouin and took with her a caravan of twenty-two camels. The people of Palmyra were impressed by her courage and gave her a crown of palm leaves. She was a bit carried away by this and later wrote: “I have been crowned Queen of the Desert. I have nothing to fear…I am the sun, the stars, the pearl, the lion, the light from heaven.”

In case you’re worried that her story is about to end with her being cruelly slain in a lonely desert, rest assured, it does not. Her end is not a happy one, but she has a few years to go yet. After that, she returned to Lebanon where she lived in several places before settling in a remote and abandoned monastery. Her lover returned to England in 1813, her doctor, in 1831. On her travels, she had come by a medieval Italian manuscript that said there were three million gold coins hidden under the ruins of a mosque at Ashkelon on the coast. She gained permission from the Ottoman authorities to excavate the site in 1815. It would be the first archaeological excavation in Palestine. Hester found no gold. What she did find was a seven foot tall headless marble statue. The thing she did next would horrify all later archaeologists and you probably won’t like it either. She had the statue smashed up and thrown in the sea. Apparently, she did this because she didn’t want to be accused of smuggling antiquities, although why she couldn’t just have left it there in one piece is beyond me.

At home in Lebanon, she became fascinated with astrology and alchemy. A fortune teller in London had once told her that she was destined to go to Jerusalem and lead the chosen people. She started to believe in the prophecy about an Islamic Messiah figure called ‘Mahdi’, and that she was destined to become his bride. She even owned a sacred horse that she believed he would ride on. It was born with a deformed spine. There was a prophecy which said that he would ride on a horse that was born saddled, and the animal’s sharply curved spine was, she thought, just like a Turkish saddle. She named the horse Layla and it was soon joined by a second horse named Lulu who she would ride alongside the Mahdi when he came for her.

Despite her eccentricities, she was generous with her hospitality. Any European traveller was well received and, when civil war broke out in the area, she gave shelter to hundreds of refugees. She fed and clothed them and, even though it nearly bankrupted her, never turned anyone away. The monastery at Djoun, which was her final home, was a hilltop house with thirty-six rooms full of secret passageways and hidden chambers. There, she kept thirty cats that her servants were forbidden to touch. In her old age, she was deeply in debt and became more and more of a recluse. Her servants resorted to stealing from her because she could not pay them. Then, in 1838, the government cut off her pension in order to pay her creditors. She sent her servants away and walled herself up in her house with her cats. She died there alone in 1839. Sad.

Fascinating story. Thanks for posting! Bronte

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading. Hester is one of my favourites.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great Post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

welcome

LikeLiked by 1 person