Today I am celebrating the birthday of Franz Mesmer who was born on this day in 1734, in a German village on the shore of Lake Constance with the lovely name of Iznang. Mesmerism is named after him. Now, the word is synonymous with hypnotism but it meant something rather different to him. He studied medicine in Vienna and learned the technique of using magnets to heal from a Hungarian astronomer called Maximilian Hell, which is an excellent name.

Today I am celebrating the birthday of Franz Mesmer who was born on this day in 1734, in a German village on the shore of Lake Constance with the lovely name of Iznang. Mesmerism is named after him. Now, the word is synonymous with hypnotism but it meant something rather different to him. He studied medicine in Vienna and learned the technique of using magnets to heal from a Hungarian astronomer called Maximilian Hell, which is an excellent name.

Belief in the healing property of magnets stretches back a long way. In the sixteenth century, a physician named Paracelsus claimed that he could cure diseases using magnets to draw out the infection. It was a belief that was partially responsible for the whole ‘weapon salve’ debacle that I have mentioned elsewhere.

Mesmer had developed a theory that all living creatures produced waves of energy that could flow from one body to another. He called this energy ‘animal magnetism’. In 1774, he created what he called a ‘magnetic tide’ in a patient who suffered from hysteria. He achieved this by having her swallow a preparation containing iron and then applying magnets to parts of her body. She reported a feeling of mysterious fluids running through her body and was free from symptoms for several hours. This is something like the feeling reported by Kasper Hauser who I mentioned last month.

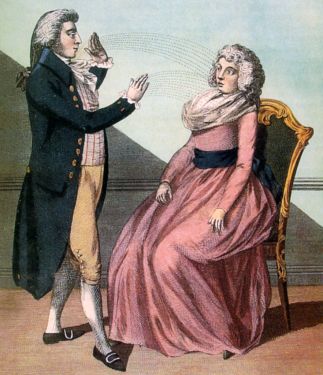

Later, he decided that he didn’t need the magnets at all but could create the same effect by moving his hands over the patient’s body. In 1777, he treated a blind pianist in an attempt to restore her sight. There was some disagreement over whether or not this had been successful. Mesmer insisted that he had cured her. Everyone else pointed out that she was still blind. He insisted that the girl and her family were pretending she was still blind, just to discredit him. He was forced to leave Vienna.

He moved to Paris where his new treatments became extremely popular. Marie Antoinette and Mozart were huge fans. To treat a single patient required him to lay his hand on the person’s belly, sometimes for several hours. His patients, who were mainly female, would often experience convulsions which he referred to as ‘crises’. These, he thought, were a necessary part of the cure. Then, he found that he could treat up to a dozen patients simultaneously by using a wooden tub filled with bottles of water (just go with this). He charged the water with animal magnetism by stroking the bottles. Then he placed one end of long wire into the neck of each bottle. The other end protruded from the tub and could be applied to the affected part of the patient. All this took place in a lavishly furnished and overheated room at the Hôtel Bullion. At first the patients would be attended by Mesmer’s assistant magnitisers, all strong young men, who would stroke the patient’s body while staring directly into their eyes. This generally led to convulsions and hysterics. Then Mesmer would appear, dressed in long purple robes embroidered with gold flowers. He carried with him a long, white magnetised rod, a wand really, and touched his patients with it to calm them. All the while, strong incense would be burning and he would play music on his glass harmonica. For him it was all about creating the right atmosphere. There was almost certainly an element, among the louche and idle rich of Paris who just liked to go along to see a woman in convulsions.

His treatments were a subject of controversy. There were plenty of people who were uncomfortable with what he was doing. Some thought him a quack, others that he had sold his soul to the Devil. In 1784 the king, Louis XVI, suspected this was all nonsense and gathered together a group of people to help him prove it. One was Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, a doctor who was an expert in pain management. So it is really rather unfair that the guillotine was going to be named after him. Another was Benjamin Franklin, who was then United States Minister to France. They devised a test to disprove his claims. Mesmer sent a deputy in his stead, a man named Charles d’Eslon. A smart move as he could claim credit if it worked but blame d’Eslon if it didn’t. The idea was that d’Eslon would magnetise a tree in Franklin’s garden and a blindfolded boy would attempt to sense which tree had been affected. The boy failed to identify the tree and the experiment ended when the boy fainted.

While mesmerism was being ridiculed by some, others were concerned that it could be used as a form of mind control. Mesmer himself left Paris a year later and rather disappeared from public life. He died in 1815. He still had many followers though. In the 1780s the Marquis de Puységur, an avid disciple of Mesmer, succeeded in putting people into a kind of trance which he called ‘somnambulism’. He found that he could question the people he put into a trance and they would answer clearly and honestly. He also found that he could control their movements. By the next century some doctors were using a ‘mesmeric trance’ to perform operations instead of using anaesthetic. In 1842 a Scottish doctor named James Braid discounted the animal magnetism idea behind mesmerism, believing it to be entirely psychological. He coined the term ‘hypnotism’ after the Greek word for sleep.

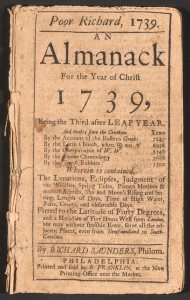

Today I want to talk about Benjamin Franklin. Benjamin Franklin was a hugely famous scientist, inventor, statesman and diplomat. But before he flew any kites in thunderstorms, invented the glass armonica or signed the United States Declaration of Independence, he was famous for something else. Franklin, like his brother before him, worked in the printing trade. On this day in 1732, he published the first edition of his ‘Poor Richard’s Almanack’ under the pseudonym of Richard Saunders.

Today I want to talk about Benjamin Franklin. Benjamin Franklin was a hugely famous scientist, inventor, statesman and diplomat. But before he flew any kites in thunderstorms, invented the glass armonica or signed the United States Declaration of Independence, he was famous for something else. Franklin, like his brother before him, worked in the printing trade. On this day in 1732, he published the first edition of his ‘Poor Richard’s Almanack’ under the pseudonym of Richard Saunders. Franklin’s almanac opens with a forward from its supposed author, Richard Saunders. He explains that he has written it because his wife thinks he is wasting his time gazing at the stars, and that if he didn’t do something profitable with his time she was going to burn all his books and scientific instruments. He goes on to say he would have written one years ago, if it weren’t for the fact that his good friend Titus Leeds always wrote one. But now, he says, the obstacle is removed because he has seen in the stars that Titus Leeds will die on October 17th at 3.29pm. He then tells us that Mr Leeds disagrees with his prediction and states that he will, in fact, die on October 26th. They have argued about this for nine years. He then entreats his readers to buy next year’s almanac to find out who was right.

Franklin’s almanac opens with a forward from its supposed author, Richard Saunders. He explains that he has written it because his wife thinks he is wasting his time gazing at the stars, and that if he didn’t do something profitable with his time she was going to burn all his books and scientific instruments. He goes on to say he would have written one years ago, if it weren’t for the fact that his good friend Titus Leeds always wrote one. But now, he says, the obstacle is removed because he has seen in the stars that Titus Leeds will die on October 17th at 3.29pm. He then tells us that Mr Leeds disagrees with his prediction and states that he will, in fact, die on October 26th. They have argued about this for nine years. He then entreats his readers to buy next year’s almanac to find out who was right.