Today I am celebrating May Day, Beltane and Walpurgisnacht. The beginning of May is a time of year when, supposedly, the warmer weather comes and everything begins to blossom and grow. Festivals have been held at this time throughout Europe for centuries. When I wrote about the founding of Rome in 753 BC, I mentioned the festival of Parilia, which involved driving a flock of sheep through a bonfire to purify them and give them protection through the following year. This is not unlike the Beltane celebrations that we find in Scotland and Ireland. In a later period the Romans held another celebration called Floralia which was dedicated to Flora, the goddess of flowers and fertility. It was a six day festival covering the end of April and the beginning of May and is probably the origin of the ‘May Queen’ tradition in England. But the Roman festival was known for its licentiousness and pleasure-seeking atmosphere. It was a festival enjoyed by the common people of Rome. Prostitutes particularly made it their own. They performed naked in the theatre and perhaps also fought in the gladiatorial arena. This doesn’t sound so much like our English festival.

Today I am celebrating May Day, Beltane and Walpurgisnacht. The beginning of May is a time of year when, supposedly, the warmer weather comes and everything begins to blossom and grow. Festivals have been held at this time throughout Europe for centuries. When I wrote about the founding of Rome in 753 BC, I mentioned the festival of Parilia, which involved driving a flock of sheep through a bonfire to purify them and give them protection through the following year. This is not unlike the Beltane celebrations that we find in Scotland and Ireland. In a later period the Romans held another celebration called Floralia which was dedicated to Flora, the goddess of flowers and fertility. It was a six day festival covering the end of April and the beginning of May and is probably the origin of the ‘May Queen’ tradition in England. But the Roman festival was known for its licentiousness and pleasure-seeking atmosphere. It was a festival enjoyed by the common people of Rome. Prostitutes particularly made it their own. They performed naked in the theatre and perhaps also fought in the gladiatorial arena. This doesn’t sound so much like our English festival.

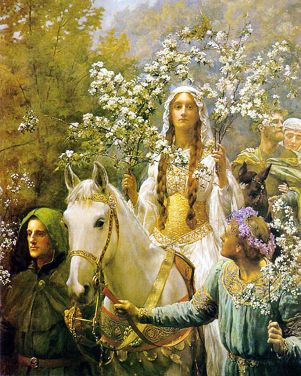

In England, the May Day festival is celebrated with dancing around a maypole, crowning a May Queen and, of course, Morris dancers. What could be more English than Morris dancers, right? The word ‘morris’ is an odd one but it is thought to derive from the word ‘Moorish’. The Moors, came originally from Morocco and settled in southern Europe in the eighth century. The term is first recorded in the fifteenth century and there seem to be comparable words in other European languages. So Morris dancing is not specifically English at all. The maypole is likely a remnant of tree worship originating amongst Germanic tribes. The dancing with ribbons is a more recent Victorian addition. It was all part of their vision of ‘Merry England’, a utopian paradise that never really existed. The crowning of a May Queen celebrates youth and new life and, as I said, probably Roman.

In Ireland and Scotland we find Beltane, which is principally a fire festival. Early sources suggest that two fires were lit and livestock were driven between them in order to provide protection for the following year. Possibly the first May bonfires were lit to drive away predators that might otherwise prove a danger to animals that were being taken to their summer pastures. Then, the fire became a ritual that would drive away all danger both natural and supernatural. Burning embers from the Beltane fire would be taken home and used to kindle a new fire in the hearth. Its ashes also had protective powers. They could be sprinkled on crops, on animals, on people. Some rituals seem to contain a memory of human sacrifice, such as leaping over the bonfire. There is an account from Scotland, mentioned in ‘The Golden Bough’, that describes a ritual in which the gathering pretended to throw someone onto the fire and afterwards spoke of him, for a while, as if he were dead.

Another feature of both May Day and Beltane was the gathering of yellow flowers to be placed at doors and windows and the construction of a May Bush. A thorn tree was be decorated with bright flowers, ribbons and painted shells. This could either be for a single household or a community endeavour. Competition between rival districts became strong, sometimes people would resort to theft. The problem of everyone trying to pinch everyone else’s bushes became so great in Ireland that the ceremony was banned in Victorian times.

In Northern Europe they celebrated Walpurgisnacht or, Hexennacht (witches night). It was celebrated on the evening of the 30th April and into the dawn of May Day. Fires were lit to drive away witches that were said to gather in the mountains on that night. In the Hartz Mountain region of Northern Germany, Walpurgisnacht celebrations sometimes gave rise to a phenomenon known as ‘the Brocken Spectre’. The Brocken is the highest peak in the Hartz mountains and almost always lost in fog. The spectre appears when a bright light casts the shadows of the observers onto the fog. It makes the shadows look enormous. They are often surrounded by a rainbow halo and generally a bit weird. The Hartz Mountains was one of the last regions in Germany to be converted to Christianity. The name Walpurgisnacht sounds like a brilliant Pagan word, but is in fact named after Saint Walpurga and is just another case of Christians spreading one of their saints all over an earlier festival. Saint Walpurga herself is disappointingly uninteresting apart from her name.

May Day celebrations are generally pastoral in nature and, as our country became more industrialised, they gradually fell out of favour. By the twentieth century they were almost gone but, due to an interest in pre-Christian religions, they have recently undergone something of a resurgence. The oldest surviving festival is the ‘Obby ‘Oss Festival in Padstow, Cornwall and probably the most notable revival of the Beltane festival has taken place at Calton Hill in Edinburgh since 1988.

Very beautiful .

LikeLike

Thank you 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Yarn Spells and commented:

Let me take this moment to add Beltaine festival at Calton Hill in Edinburgh to my “if I win the lottery” bucket list.

Thank you for this bit of knowledge and history of our Spring Fire celebration.

Mahalo.

LikeLike