Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II, was born on this day in 1552 in Vienna. Rudolph was also King of Germany, King of Bohemia and King of Hungary. He became something of a recluse, rarely leaving his palace in Prague. He ruled at a difficult time when, as Holy Roman Emperor, he was meant to be Catholic, but a lot of his subjects were not. He tried to occupy the middle ground and it didn’t really work out too well for him. He was eventually deposed by his more ambitious brother. All this makes him sound rather dull, but he really wasn’t.

Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II, was born on this day in 1552 in Vienna. Rudolph was also King of Germany, King of Bohemia and King of Hungary. He became something of a recluse, rarely leaving his palace in Prague. He ruled at a difficult time when, as Holy Roman Emperor, he was meant to be Catholic, but a lot of his subjects were not. He tried to occupy the middle ground and it didn’t really work out too well for him. He was eventually deposed by his more ambitious brother. All this makes him sound rather dull, but he really wasn’t.

Rudolf was an enthusiastic patron of both the arts and sciences. This meant his court harboured all sorts of interesting people. Under his rule, Prague had a reputation for being full of dissidents, heretics and heliocentrists. The idea that the earth might go round the sun, instead of the other way round was not a popular one. In 1599, he made Tycho Brahe, who is probably my favourite astronomer ever, his court astronomer, after he was exiled from his home country of Denmark. But Rudolph was also fascinated by alchemy and the occult. Both of these subjects were, at the time, every bit as credible as astronomy. In the 1580s, he was visited by the famous mathematician and alchemist John Dee along with his questionable friend Edward Kelley, who Rudolph later locked up in a castle.

The Emperor was an extremely keen collector of both art objects and scientific instruments. As well as collecting well-known artists like Dürer and Brueghel, he commissioned many new pieces. This unusual portrait on the left is Rudolph as Vertumnus, the Roman god of the seasons. The artist’s name is Giuseppe Arcimboldo, he did a lot of paintings like this, but mostly they have titles like ‘winter’ or ‘the librarian’. This is the only one I could find that is of a specific person.

The Emperor was an extremely keen collector of both art objects and scientific instruments. As well as collecting well-known artists like Dürer and Brueghel, he commissioned many new pieces. This unusual portrait on the left is Rudolph as Vertumnus, the Roman god of the seasons. The artist’s name is Giuseppe Arcimboldo, he did a lot of paintings like this, but mostly they have titles like ‘winter’ or ‘the librarian’. This is the only one I could find that is of a specific person.

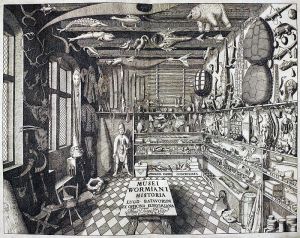

Rudolf amassed an amazing ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’ that included one hundred and twenty astronomical and geometrical instruments and more than sixty clocks. His collection was the finest in Europe and it occupied three large rooms of his palace. As the private collection of a recluse, not many people got to see it, so we can’t be sure of everything that it contained. Certainly he kept a live lion and a tiger, which roamed freely about the castle. We know this because there are documents relating to the payment of compensation to those who had been attacked by them or, if it had gone particularly badly, to their families. Rudolf himself insisted that he owned a grain of earth from which God made Adam, two nails from Noah’s Ark, a basilisk and some dragons.

Rudolf never married, but it is rumoured that he had numerous affairs at court with both men and women. He had several illegitimate children, one of whom seems to have suffered from schizophrenia and did some terrible things. Rudolf was a member of the Habsburg dynasty, who suffered terribly from inbreeding and do not have a happy history of mental stability. Rudolph himself seems to have suffered from bouts of melancholia, which was common in his family. Two of his favourite objects were a cup made of agate, which he believed to be the Holy Grail, and a six foot long horn, which came from a narwhal, but Rudolf thought it had belonged to a unicorn. When he was at his lowest he liked to take these two things, draw himself a magic circle with a Spanish sword, then just sit in it.

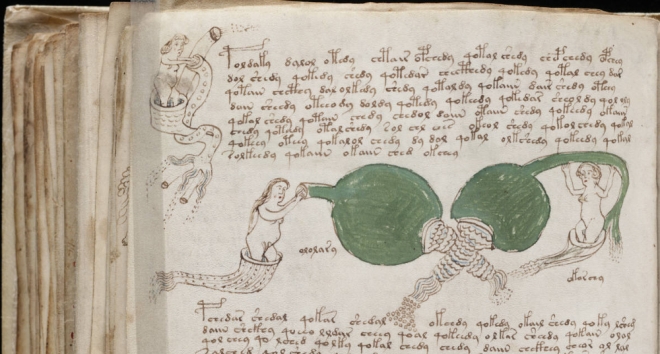

Some believe him to be one of the owners the Voynich Manuscript, a very interesting document which I mentioned briefly when I wrote about Edward Kelley. It has been carbon dated to some time in the early fifteenth century and is written in an unknown language. It has defied all attempts to translate it. Most of the illustrations are botanical and there are some with what look like star charts. But some are really weird. There are a lot of drawings of naked women that also feature an elaborate system of pipes. They seem to be conveying something really specific, but we have no idea what. So, naturally, they make everyone who sees it really want to know what it says. It seems to contain information about plants, medicine, biology, astronomy and cosmology. It doesn’t appear to be written in code, but rather in some, now lost, language that is possibly Middle Eastern in origin, but no other examples of the language have ever been found. If you’ve never come across it before, you can find a facsimile here

.

.

Rudolf, as you may gather, was a deeply superstitious man. Tycho Brahe once informed him that he shared a horoscope with his favourite lion cub. When it died, years later, the Emperor shut himself up in his rooms and refused all medical attention. He died three days later. His successors were less enthusiastic about his collection. It was packed away and forgotten about. Later, much of it was stolen when Swedish troops attacked Prague Castle in 1648 and many of its items later ended up in the hands of Queen Christina of Sweden.

Today I am celebrating the birthday of Maria Sibylla Merian, who was born in 1647 in Frankfurt. Maria was a painter and a naturalist with a particular interest in insects. Her family ran one of the largest publishing houses in seventeenth century Europe. When she was three, her father died and her mother remarried. Her step father was a still life painter named Jacob Marrel and he encouraged her to paint. At thirteen, she began to paint the plants and caterpillars that she found near her home. She became interested in their life cycles and what sort of plants they fed on.

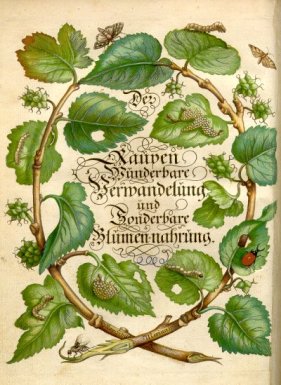

Today I am celebrating the birthday of Maria Sibylla Merian, who was born in 1647 in Frankfurt. Maria was a painter and a naturalist with a particular interest in insects. Her family ran one of the largest publishing houses in seventeenth century Europe. When she was three, her father died and her mother remarried. Her step father was a still life painter named Jacob Marrel and he encouraged her to paint. At thirteen, she began to paint the plants and caterpillars that she found near her home. She became interested in their life cycles and what sort of plants they fed on. At sixteen, she married one of her step father’s apprentices but, although they had two daughters, it wasn’t a particularly happy union. They moved to Nuremberg and she continued to paint, her flower illustrations were also used as designs for embroidery. Also she gave drawing lessons to young women from wealthy families. This gave her access to a lot of splendid gardens where she could continue her insect studies. Between 1675 and 1677 she published three volumes of flower paintings called ‘Neues Blumenbuch’ (New book of flowers). In 1679 she published a book about the metamorphosis of insects. ‘Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung’ (The Caterpillars’ Marvellous Transformation and Strange Floral Food) was particularly popular amongst high society, especially so because it was written in German. It was ignored by scientists for the same reason. They couldn’t take it seriously unless it was in Latin.

At sixteen, she married one of her step father’s apprentices but, although they had two daughters, it wasn’t a particularly happy union. They moved to Nuremberg and she continued to paint, her flower illustrations were also used as designs for embroidery. Also she gave drawing lessons to young women from wealthy families. This gave her access to a lot of splendid gardens where she could continue her insect studies. Between 1675 and 1677 she published three volumes of flower paintings called ‘Neues Blumenbuch’ (New book of flowers). In 1679 she published a book about the metamorphosis of insects. ‘Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung’ (The Caterpillars’ Marvellous Transformation and Strange Floral Food) was particularly popular amongst high society, especially so because it was written in German. It was ignored by scientists for the same reason. They couldn’t take it seriously unless it was in Latin. After six years of living in a religious community, where it turned out her husband wasn’t welcome, she moved to Amsterdam with her daughters in 1691 and was divorced from her husband a year later. There she continued to teach. One of her pupils was Rachel Ruysch, daughter of

After six years of living in a religious community, where it turned out her husband wasn’t welcome, she moved to Amsterdam with her daughters in 1691 and was divorced from her husband a year later. There she continued to teach. One of her pupils was Rachel Ruysch, daughter of

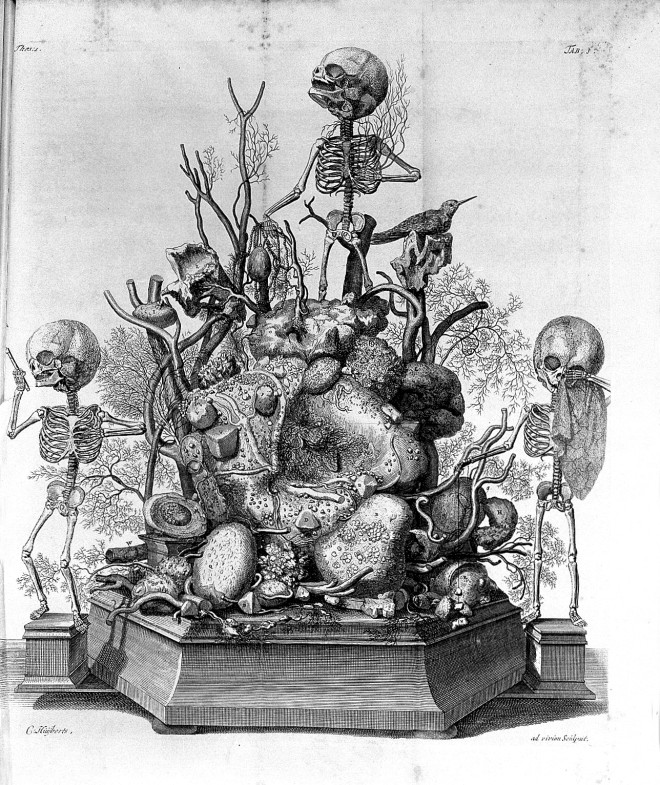

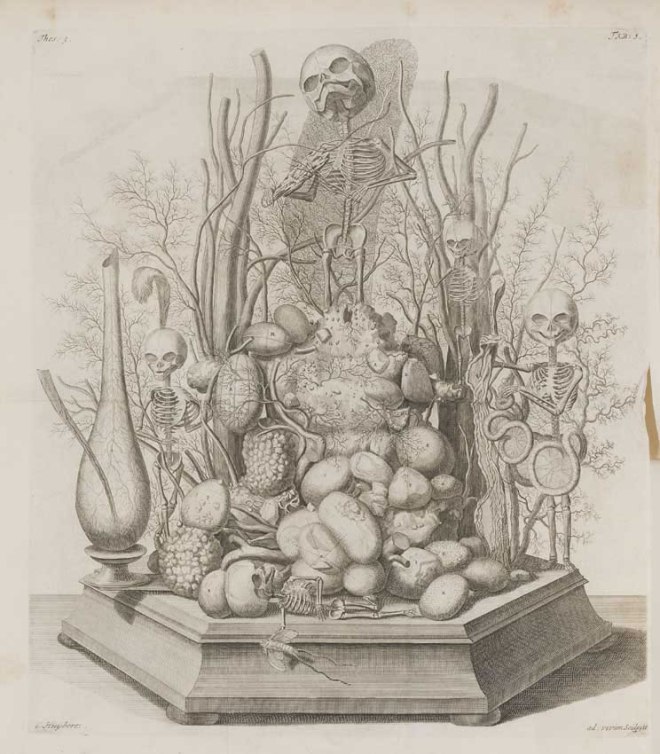

Today is the birthday of Frederick Ruysch who was born in 1638 in The Hague. Someone who had himself painted pulling the insides out of a dead baby might seem like an unlikely candidate for ‘Why Today is Brilliant’, but bear with me. Ruysch is the last of three peculiar Dutch anatomists who I first stumbled upon last summer. They all studied at the university of Leiden in the 1660s. I have written about

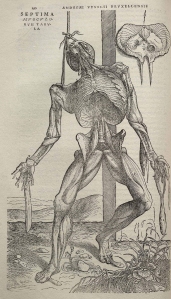

Today is the birthday of Frederick Ruysch who was born in 1638 in The Hague. Someone who had himself painted pulling the insides out of a dead baby might seem like an unlikely candidate for ‘Why Today is Brilliant’, but bear with me. Ruysch is the last of three peculiar Dutch anatomists who I first stumbled upon last summer. They all studied at the university of Leiden in the 1660s. I have written about  His work was not entirely unprecedented. There were anatomical texts that showed bodies in dramatic poses. Take a look at this one from ‘

His work was not entirely unprecedented. There were anatomical texts that showed bodies in dramatic poses. Take a look at this one from ‘

The British Museum opened to the public for the first time on this day in 1759. It was the world’s first national museum. Unlike other national collections at the time, it didn’t belong to a king or to the Church and was freely open to the public. The museum was opened after a man called Sir Hans Sloane left his huge cabinet of curiosities to King George II, on condition that it be available to the public. As he had spent a lifetime gathering over 71,000 items, he wanted his collection to be kept intact. Sloane was a physician who began collecting plants and books about plants, but his cabinet also included coins, jewellery, fish, birds, mammals, scientific instruments, paintings. His interests were wide ranging. After working in Jamaica, he also gathered a lot of cultural artefacts from the Americas. He gave his cabinet in exchange for £20,000 which was to be given to his two daughters. It was actually worth around £80,000 but still The King was reluctant, he wasn’t a fan of the arts and sciences. In fact he hated ‘bainting and boetry.’ The government weren’t terribly keen either but eventually they raised the money with a public lottery. For many years after it opened, it was still referred to as a ‘cabinet’ rather than a museum.

The British Museum opened to the public for the first time on this day in 1759. It was the world’s first national museum. Unlike other national collections at the time, it didn’t belong to a king or to the Church and was freely open to the public. The museum was opened after a man called Sir Hans Sloane left his huge cabinet of curiosities to King George II, on condition that it be available to the public. As he had spent a lifetime gathering over 71,000 items, he wanted his collection to be kept intact. Sloane was a physician who began collecting plants and books about plants, but his cabinet also included coins, jewellery, fish, birds, mammals, scientific instruments, paintings. His interests were wide ranging. After working in Jamaica, he also gathered a lot of cultural artefacts from the Americas. He gave his cabinet in exchange for £20,000 which was to be given to his two daughters. It was actually worth around £80,000 but still The King was reluctant, he wasn’t a fan of the arts and sciences. In fact he hated ‘bainting and boetry.’ The government weren’t terribly keen either but eventually they raised the money with a public lottery. For many years after it opened, it was still referred to as a ‘cabinet’ rather than a museum. There had been many cabinets of curiosity all over Europe since the sixteenth century. They were really the forerunners of the museum. They sound like small things, kept in cupboards, but actually they were whole rooms stuffed with anything and everything that the collector was interested in. They usually belonged to royalty or nobility. It was its owner’s world in microcosm and represented his power and influence. Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II had one that included a live lion and tiger who roamed about freely. We know this because there are records of the compensation paid to those injured by the animals or to the families of their victims.

There had been many cabinets of curiosity all over Europe since the sixteenth century. They were really the forerunners of the museum. They sound like small things, kept in cupboards, but actually they were whole rooms stuffed with anything and everything that the collector was interested in. They usually belonged to royalty or nobility. It was its owner’s world in microcosm and represented his power and influence. Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II had one that included a live lion and tiger who roamed about freely. We know this because there are records of the compensation paid to those injured by the animals or to the families of their victims. The original museum was located in a seventeenth century mansion called Montagu House which was on the same site as the present museum. Before it opened, there was much debate among the trustees over who should and should not be allowed to see it. They weren’t very sure about letting in servants, or members of the lower classes in general, in case they upset the museum’s more refined visitors. Eventually they decided just to take a good look at everyone. If they were smartly dressed, well-behaved and didn’t appear to be under the age of ten, then they would be issued a ticket and allowed in. But only in groups of not more than fifteen and they must be accompanied at all times. One group each hour between 10 am and 2 pm. That’s a whole seventy-five visitors a day.

The original museum was located in a seventeenth century mansion called Montagu House which was on the same site as the present museum. Before it opened, there was much debate among the trustees over who should and should not be allowed to see it. They weren’t very sure about letting in servants, or members of the lower classes in general, in case they upset the museum’s more refined visitors. Eventually they decided just to take a good look at everyone. If they were smartly dressed, well-behaved and didn’t appear to be under the age of ten, then they would be issued a ticket and allowed in. But only in groups of not more than fifteen and they must be accompanied at all times. One group each hour between 10 am and 2 pm. That’s a whole seventy-five visitors a day.