Hooray! We’ve all made it (safely I hope) into another New Year. So firstly, I wish for you more of the things you enjoyed last year, and less of the things you didn’t like, in the year ahead. New Year is a time for new beginnings, for letting go past enmities and troubles and making a fresh start. Perhaps you opened your back door on the stroke of midnight to make sure the old year made a swift exit. In my family, the 1960s and 70s found my dad standing outside the front door clutching a piece of coal and a silver coin waiting to be let in as a ‘first-footer’. We needed a dark-haired man to be first over the threshold on New Year’s Day to bring luck for the following year and, fortunately, he fitted the bill perfectly. The coal represented warmth, the coin, fortune. It is an old, and predominantly northern tradition that can sometimes involve a piece of bread to represent food and some greenery to ensure long life for everyone.

Hooray! We’ve all made it (safely I hope) into another New Year. So firstly, I wish for you more of the things you enjoyed last year, and less of the things you didn’t like, in the year ahead. New Year is a time for new beginnings, for letting go past enmities and troubles and making a fresh start. Perhaps you opened your back door on the stroke of midnight to make sure the old year made a swift exit. In my family, the 1960s and 70s found my dad standing outside the front door clutching a piece of coal and a silver coin waiting to be let in as a ‘first-footer’. We needed a dark-haired man to be first over the threshold on New Year’s Day to bring luck for the following year and, fortunately, he fitted the bill perfectly. The coal represented warmth, the coin, fortune. It is an old, and predominantly northern tradition that can sometimes involve a piece of bread to represent food and some greenery to ensure long life for everyone.

New Year has not always been on January 1st, but it has always been a time for taking stock of your life and starting anew, as you mean to go on. In Ancient Babylonia the year began at the spring equinox. It was an eleven day festival that involved the king being stripped of his regalia and slapped around by a priest until he cried, just to make sure he respected the gods and didn’t get too above himself. Sadly, this ritual has now fallen from favour. It might have been fun to see Trump stripped to his underwear and slapped around Washington National Cathedral by its bishop as a sort of pre-inauguration ceremony. I have no idea weather the bishop would be up for this, wikipedia has little to say about the bishops political leanings. In fact, it has very little to say about her at all, but it’s a cheery thought to begin 2017.

Ordinary people would try to placate their gods by making promises to them, typically, to return borrowed farm equipment. We also often make promises to be better people, in the form of New Year’s Resolutions. Though, if the Ancient Babylonians were as good at sticking to their resolve as we are, there were probably plenty of farmers who never saw their ploughs again.

It was the Romans who fixed New Year’s Day as January 1st. They made it sacred to their god Janus. Perhaps the whole month of January is named after him. Janus is the god of gateways, of beginnings and of transitions. He has two faces, one looking forwards and the other backwards. He looks to the future but also the past. So he sits quite well at the threshold between one year and the next. The Romans believed that the beginning of anything held omens for the whole. So it was important to greet everyone cheerfully and to give and receive small gifts. If you want to follow their lead, you should also devote a little time to your usual work. Not too much, don’t go overboard and leave the house or anything.

It was the Romans who fixed New Year’s Day as January 1st. They made it sacred to their god Janus. Perhaps the whole month of January is named after him. Janus is the god of gateways, of beginnings and of transitions. He has two faces, one looking forwards and the other backwards. He looks to the future but also the past. So he sits quite well at the threshold between one year and the next. The Romans believed that the beginning of anything held omens for the whole. So it was important to greet everyone cheerfully and to give and receive small gifts. If you want to follow their lead, you should also devote a little time to your usual work. Not too much, don’t go overboard and leave the house or anything.

In England the date on which the New Year started has been confusing. Although most people considered New Year’s day to be January 1st, Samuel Pepys certainly did, the year legally did not begin until March 25th. Between the seventh and twelfth centuries, it began on December 25th. Then, there was the liturgical year, which began on the first Sunday of Advent. Most of Europe began to accept January 1st as the beginning of the New Year in the sixteenth century. Scotland adopted it is 1600 to keep in line with other “well governit commonwealths” in Europe, which probably explains why they’re so much better at New Year than we are. They’ve had more practice. In England we stuck with March 25th until we adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1752. It must have been difficult. In the days surrounding Christmas and New Year, it’s hard enough to know what day it is, without wondering what year it is as well.

Yesterday, I wrote about money and how it is worth nothing until you exchange it for something else. Today, I want to look at some of the people who didn’t get round to spending what they had while they were alive. Writers have long been fascinated by misers. Aesop, writing in the seventh or sixth century BC, tells us a story of a miser who buried his gold. But he came back to look at it every day and someone saw him, dug up the gold and stole it. The miser was distraught at the loss of his wealth. His neighbour consoled him by telling him that he might just as well bury a stone instead, or even just come back each day and look at the empty hole. Because he wasn’t using his gold, it would really be exactly the same thing. Buried gold is as useless as stone or an hole in the ground.

Yesterday, I wrote about money and how it is worth nothing until you exchange it for something else. Today, I want to look at some of the people who didn’t get round to spending what they had while they were alive. Writers have long been fascinated by misers. Aesop, writing in the seventh or sixth century BC, tells us a story of a miser who buried his gold. But he came back to look at it every day and someone saw him, dug up the gold and stole it. The miser was distraught at the loss of his wealth. His neighbour consoled him by telling him that he might just as well bury a stone instead, or even just come back each day and look at the empty hole. Because he wasn’t using his gold, it would really be exactly the same thing. Buried gold is as useless as stone or an hole in the ground. Over the last year, I’ve mentioned so many people who occupy a rather grey area between belief in magic and the beginnings of modern science, that I cannot let today go by without telling you that it is John Dee’s birthday. Dee was born in 1527, in the Tower Ward of the City of London. Both his parents were Welsh and his surname derives from the Welsh word for black, ‘du’. John Dee is black by name and black by reputation. For hundreds of years, he has been mainly remembered as a magician in the court of Queen Elizabeth I. Shakespeare probably modelled his character of Prospero on John Dee. While it’s true that he did spend a lot of the last thirty years of his life trying to speak with angels, this opinion is rather unfair. Dee was an incredibly clever man.

Over the last year, I’ve mentioned so many people who occupy a rather grey area between belief in magic and the beginnings of modern science, that I cannot let today go by without telling you that it is John Dee’s birthday. Dee was born in 1527, in the Tower Ward of the City of London. Both his parents were Welsh and his surname derives from the Welsh word for black, ‘du’. John Dee is black by name and black by reputation. For hundreds of years, he has been mainly remembered as a magician in the court of Queen Elizabeth I. Shakespeare probably modelled his character of Prospero on John Dee. While it’s true that he did spend a lot of the last thirty years of his life trying to speak with angels, this opinion is rather unfair. Dee was an incredibly clever man.

Today is the birthday of Sir Kenelm Digby, who was born in 1603 at Gayhurst in Buckinghamshire. Digby was from a wealthy family, but he had a poor start in life. His father was one of the men executed for the Gunpowder Plot. I’ve not mentioned him before, but I’ve come across Digby often in my research. He turns up in all sorts of odd places, I’ve found him fighting duels, practising sympathetic magic, being a founder member of the Royal Society, authoring a cookery book and tragically mourning the death of his wife in quite weird way. So I thought we could have a proper look at him today.

Today is the birthday of Sir Kenelm Digby, who was born in 1603 at Gayhurst in Buckinghamshire. Digby was from a wealthy family, but he had a poor start in life. His father was one of the men executed for the Gunpowder Plot. I’ve not mentioned him before, but I’ve come across Digby often in my research. He turns up in all sorts of odd places, I’ve found him fighting duels, practising sympathetic magic, being a founder member of the Royal Society, authoring a cookery book and tragically mourning the death of his wife in quite weird way. So I thought we could have a proper look at him today.

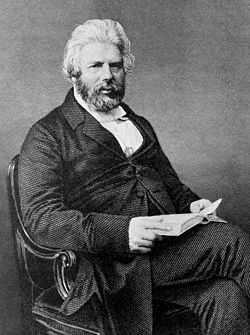

Today, I am celebrating the birthday of Robert Chambers who was born in Peebles in the Scottish Borders in 1802. He and his brother William founded W & R Chambers Publishing, who eventually produced Chambers Dictionary. That’s my favourite dictionary, but that’s not why I wanted to tell you about him. I discovered Robert a year ago when I was writing on Tumblr and he has been with me almost every day since. But I’ll get to that in a minute.

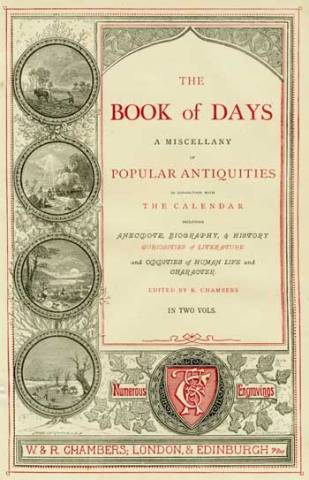

Today, I am celebrating the birthday of Robert Chambers who was born in Peebles in the Scottish Borders in 1802. He and his brother William founded W & R Chambers Publishing, who eventually produced Chambers Dictionary. That’s my favourite dictionary, but that’s not why I wanted to tell you about him. I discovered Robert a year ago when I was writing on Tumblr and he has been with me almost every day since. But I’ll get to that in a minute. Robert Chambers’ last work was ‘Chambers Book of Days’ published in 1864. It was subtitled: ‘A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, Including Anecdote, Biography, & History, Curiosities of Literature and Oddities of Human Life and Character’. It’s a massive work that runs to two volumes each with more than 840 pages. It contains, for each day of the year, a list of the births and deaths of notable people and a list of the saints associated with that day. Then underneath are a number of short essays about the some of the people, or the events that happened on that date. When I discovered Robert, I was happy to have found a kindred spirit. His undertaking was much larger than my meagre effort. He wrote around two thousand essays for his ‘Book of Days’ and he didn’t even have the internet to help him. It seems his family all thought the huge amount of work he put into his book contributed to his early death in 1871. Despite this warning from history, I have pressed on with my project and now have only twelve days to go.

Robert Chambers’ last work was ‘Chambers Book of Days’ published in 1864. It was subtitled: ‘A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, Including Anecdote, Biography, & History, Curiosities of Literature and Oddities of Human Life and Character’. It’s a massive work that runs to two volumes each with more than 840 pages. It contains, for each day of the year, a list of the births and deaths of notable people and a list of the saints associated with that day. Then underneath are a number of short essays about the some of the people, or the events that happened on that date. When I discovered Robert, I was happy to have found a kindred spirit. His undertaking was much larger than my meagre effort. He wrote around two thousand essays for his ‘Book of Days’ and he didn’t even have the internet to help him. It seems his family all thought the huge amount of work he put into his book contributed to his early death in 1871. Despite this warning from history, I have pressed on with my project and now have only twelve days to go. Yesterday’s post was a big one, so I’m going to try to keep it short today. Today is the birthday of not one, but two Gothic novelists. Ann Radcliffe, who was born in 1764 and Matthew Gregory Lewis, who was born in 1775. Both, as far as I can tell, in London.

Yesterday’s post was a big one, so I’m going to try to keep it short today. Today is the birthday of not one, but two Gothic novelists. Ann Radcliffe, who was born in 1764 and Matthew Gregory Lewis, who was born in 1775. Both, as far as I can tell, in London.

On this day in 1919, the R34 airship touched down in Mineola, Long Island and became the first airship to cross the Atlantic Ocean and the first aircraft to cross it from west to east. The R34 was ninety-two feet high and the length of two football fields. Her crew nicknamed her ‘Tiny’.

On this day in 1919, the R34 airship touched down in Mineola, Long Island and became the first airship to cross the Atlantic Ocean and the first aircraft to cross it from west to east. The R34 was ninety-two feet high and the length of two football fields. Her crew nicknamed her ‘Tiny’.

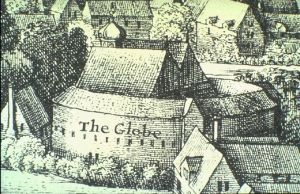

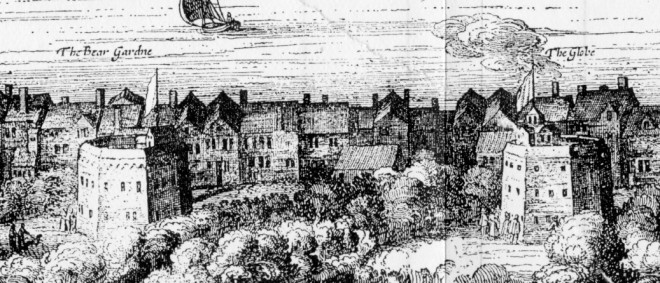

Today, I want to tell you about the Globe Theatre, in Southwark. The theatre where William Shakespeare worked and where his plays were performed. It opened in 1599, I don’t know the exact date, but I do know when it burned down and it was on this day in 1613.

Today, I want to tell you about the Globe Theatre, in Southwark. The theatre where William Shakespeare worked and where his plays were performed. It opened in 1599, I don’t know the exact date, but I do know when it burned down and it was on this day in 1613.

Today, I am in a bit of a quandary. The thing that I was going to tell you about did, I’ve since discovered, not happen on this day at all, but on the 25th. Never mind, it’s sometimes easy mistake a 5 for an 8 and if you wanted to know about the Newbury Coat, which was a bet about being able to shear a sheep, spin and weave its wool and make a coat out of it in a single day, you’ll find it

Today, I am in a bit of a quandary. The thing that I was going to tell you about did, I’ve since discovered, not happen on this day at all, but on the 25th. Never mind, it’s sometimes easy mistake a 5 for an 8 and if you wanted to know about the Newbury Coat, which was a bet about being able to shear a sheep, spin and weave its wool and make a coat out of it in a single day, you’ll find it

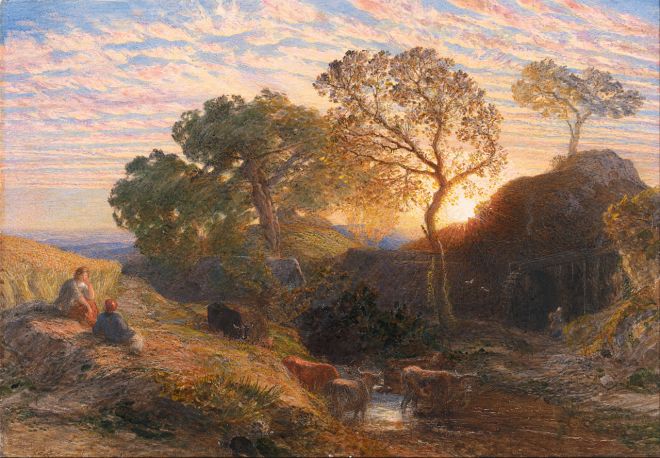

Incidentally, Leigh Hunt was not big on Royalty either. He was once arrested and tried for saying something extremely uncomplimentary, but also true, about the Prince Regent. He was promised that he would be let off, if he promised not to say anything else rude about the future George IV. He politely declined and spent two years in prison. He bore it well. He had his room papered with rose trellises and the ceiling painted like the sky. He had his books, he had a piano and he had lots of visitors. His friend Charles Lamb said there was: “no other such room, except in a fairy tale.”

Incidentally, Leigh Hunt was not big on Royalty either. He was once arrested and tried for saying something extremely uncomplimentary, but also true, about the Prince Regent. He was promised that he would be let off, if he promised not to say anything else rude about the future George IV. He politely declined and spent two years in prison. He bore it well. He had his room papered with rose trellises and the ceiling painted like the sky. He had his books, he had a piano and he had lots of visitors. His friend Charles Lamb said there was: “no other such room, except in a fairy tale.”