Today, I want to tell you about the Globe Theatre, in Southwark. The theatre where William Shakespeare worked and where his plays were performed. It opened in 1599, I don’t know the exact date, but I do know when it burned down and it was on this day in 1613.

Today, I want to tell you about the Globe Theatre, in Southwark. The theatre where William Shakespeare worked and where his plays were performed. It opened in 1599, I don’t know the exact date, but I do know when it burned down and it was on this day in 1613.

The Globe was built to house an acting company called the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. It was owned, for the most part, by the company’s lead actor, Richard Burbage and his brother Cuthbert. But Shakespeare owned a one eighth share in the project. The actors’ previous home in Shoreditch, north of the City, had been one of the first, and certainly the most successful permanent theatres to be built in England since Roman times. I can tell you where it was: between Alice Daridge’s garden and the Earl of Rutland’s oat barn. Just near the Great Horse Pond, next to the common sewer and a slaughterhouse. Not that this really tells you much about it’s geographical location, but it does give you some idea of what it might have been like. It opened in 1576 and was called, simply, ‘The Theatre’. But they had run into problems. The Theatre had been built by Richard and Cuthbert’s father James Burbage and a man named Mr Brayne who was his brother-in-law. After both men died, there was a huge falling-out over who owned what. Added to this, the Theatre was built on land that was leased from a man called Giles Allen. Allen was a staunch Puritan who wasn’t keen on theatre and, when the lease ran out in 1596, he refused to renew it. What’s more, he claimed that the building now belonged to him too.

The Burbages side-stepped the whole problem on the night of December 28th 1598. Giles Allen was away celebrating Christmas at his country residence and the Burbages, along with a carpenter called Peter Street and a few others, probably including Shakespeare, simply stole the building. They assured onlookers that they were renovating it, but in fact, they carted away all the massive oak beams and stored them in the carpenter’s warehouse over the winter. When the weather improved, they used the beams to build themselves a new theatre across the river at Southwark.

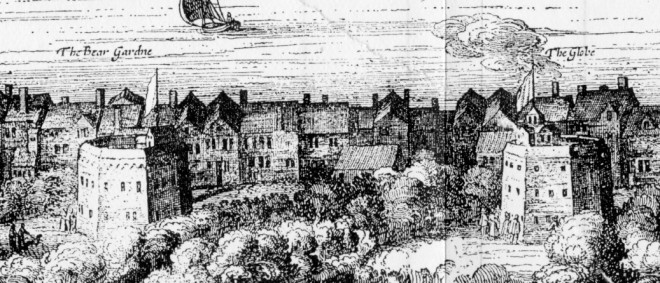

The site of the Globe theatre wasn’t great either. It was prone to flooding, especially at high tide and they had to build a sort of raised bank to protect it. Also, one of the other attractions on offer nearby was bear-baiting. We have an account from a Swiss tourist called Thomas Platter, who visited in 1599. He said that he saw twelve bears and a hundred and twenty mastiffs and it absolutely stank because of all the offal that was fed to the dogs. He also went to see a play. It was Julius Caesar and it may have been the first play performed at the Globe. Thomas tells us that the audience could stand and watch from the courtyard for one penny. For two, you could get a seat in the galleries and for three, you could get a cushion as well and a seat where everyone could see you. He describes the actors as lavishly dressed and explains why this was. Lords and knights, he says, tended to bequeath their best clothes to their servants. But they were much too fancy for a servant to wear, so they sold them and actors bought them.

The theatre, as I said, caught fire in 1613. It was during a performance of Henry VIII. It broke out after the firing of a theatrical cannon. Some of the material fired from the cannon reached the thatched roof of the building where it smouldered unheeded for a while. The fire spread inside the thatch and soon the whole roof was on fire. The entire building was burned to the ground in less two hours. It seems no one was hurt though, which was lucky as the theatre could host up to three thousand spectators and there were only two small doors for everyone to get out. According to an eyewitness the only casualty was a man whose breeches caught fire, but it was quickly put out by someone pouring a bottle of ale over them.

The theatre was quickly rebuilt on the same foundations, but this time, they sensibly built it with a tiled roof. The Globe Theatre was in use, apart from periods of closure due to outbreaks of bubonic plague, until all the theatres were closed by down the Puritans in 1642. It was demolished two or three years later. We have a pretty good idea of what the theatre looked like because we have a beautiful reconstruction of it, only 750 ft from where the original stood. It is the first thatched building to have been allowed in London since the Great Fire of 1666.

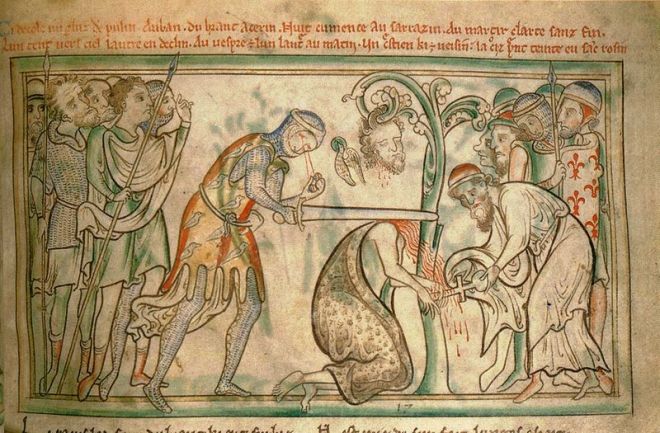

Today is the feast day on Saint Alban, who was the first recorded Christian martyr in Britain. The actual year this happened is not clear, but it is placed somewhere between 209 and 304 AD, during the time that the Romans still occupied Britain. In fact, we cant be certain that he existed at all. There is a vague mention of an unnamed somebody who sounds a bit like him, dating from the end of the fourth century, but we mainly know about him from a visiting bishop called Germanus.

Today is the feast day on Saint Alban, who was the first recorded Christian martyr in Britain. The actual year this happened is not clear, but it is placed somewhere between 209 and 304 AD, during the time that the Romans still occupied Britain. In fact, we cant be certain that he existed at all. There is a vague mention of an unnamed somebody who sounds a bit like him, dating from the end of the fourth century, but we mainly know about him from a visiting bishop called Germanus.

Today, I want to tell you about the Great Fire of Chudleigh which happened in 1807. Chudleigh is a small town in Devon, and, like the Great Fire of London, the blaze began in a bakery. At around noon, a pile of gorse stacked near a baking oven caught light. Normally, it might have been easily controlled, but there had been a long spell of dry weather. Then, a breeze blew up which carried burning flakes from the fire to neighbouring properties. Many of the dwellings had thatched roofs which had become tinder dry in the hot sun and they quickly caught light. The same breeze then carried large pieces of burning thatch and soon, three whole streets were on fire.

Today, I want to tell you about the Great Fire of Chudleigh which happened in 1807. Chudleigh is a small town in Devon, and, like the Great Fire of London, the blaze began in a bakery. At around noon, a pile of gorse stacked near a baking oven caught light. Normally, it might have been easily controlled, but there had been a long spell of dry weather. Then, a breeze blew up which carried burning flakes from the fire to neighbouring properties. Many of the dwellings had thatched roofs which had become tinder dry in the hot sun and they quickly caught light. The same breeze then carried large pieces of burning thatch and soon, three whole streets were on fire.