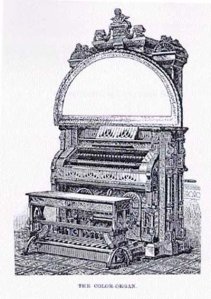

Today I am celebrating the patenting of the first portable typewriter in 1892 and I am writing it on my first portable computer, for reasons that may become clear later. Also, I am celebrating the fact that it was invented by a man named George Canfield Blickensderfer. What a brilliant name. Here it is on the right… The typewriter, not my computer. I rather like it. It has some sort of insect quality that I can’t quite put my finger on. It looks as though it belongs in more in David Cronenberg’s ‘Naked Lunch’ than in the real world.

Today I am celebrating the patenting of the first portable typewriter in 1892 and I am writing it on my first portable computer, for reasons that may become clear later. Also, I am celebrating the fact that it was invented by a man named George Canfield Blickensderfer. What a brilliant name. Here it is on the right… The typewriter, not my computer. I rather like it. It has some sort of insect quality that I can’t quite put my finger on. It looks as though it belongs in more in David Cronenberg’s ‘Naked Lunch’ than in the real world.

Blickensderfer came up with the idea for a portable writing machine while he was travelling about selling his previous invention, which was also brilliant, but rather hard to describe. It was a kind of tiny railway that was used in large department stores; a store carrier service that could transport packages and money from different store counters to a central packing station and back. So you could take something to the counter and pay for it. It would be sent off in a little basket to a back room somewhere. Then come whizzing back, all wrapped up, along with your change.

He did quite a lot of travelling whilst he was selling his store carriers and he thought how useful it could be to write letters and invoices whilst on the train or in a hotel room. There were other typing machines around but mostly, they had two problems. Their design meant that you couldn’t see what you were typing until you scrolled the paper up and also they were very heavy and definitely desk bound. Blickensderfer invented the laptop model. You could see the letters as you typed them. He managed to redesign it so that it had fewer parts; only 250 as opposed to 2,500. He also made it much lighter, it was one fifth of the weight of other typewriters. The letters were embossed on a wheel instead of having a separate type bar attached to each key.  This made it good for export as the type wheel was interchangeable and could be used for different languages. The Blickensderfer could be modified to type in Slovak, in Armenian, in Hebrew. His wheel arrangement was reinvented in 1961 by IBM in their ‘Selectric’ model.

This made it good for export as the type wheel was interchangeable and could be used for different languages. The Blickensderfer could be modified to type in Slovak, in Armenian, in Hebrew. His wheel arrangement was reinvented in 1961 by IBM in their ‘Selectric’ model.

This interchangeable ball idea seems like a wonderfully easy solution to a person who may, for example, have tried to download Windows 10 onto her laptop which subsequently crashed potentially taking over a year’s worth of blog notes with it. So much easier to change your operating system in the 1890s.

Blickensderfer exhibited his machine at a trade fair at the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893. He employed his secretary, a lady called May Munson who had bright red hair, to demonstrate the machine. May and her typewriter attracted so much attention that it seems all the other typewriter manufacturers packed up their booths. The exhibition brought him hundreds of orders and his first export deals. By 1896, he was producing 10,000 machines a year.

Instead of using the QWERTY keyboard he used a different arrangement with the most common keys located on the bottom row. the idea was, that if the typist had their fingers mostly on the bottom row of keys, they wouldn’t have to move their hands as much and typing would be quicker. Like other alternative keyboard layouts, it didn’t really last. His alternate layout is known as DHIATENSOR, for obvious reasons if you look at one.

In 1900, he invented the the first electric typewriter. Although I read that its speed and efficiency was not matched until IBM came along with their reinvented writing ball, it doesn’t seem to have been very popular. Very few are still in existence.

Today I am celebrating the life of Elisha Graves Otis who, on this day in 1857, installed the first elevator that was able to safely carry human passengers at 448 Broadway, Manhattan. The E V Haughwout Building didn’t strictly need an elevator. At five storeys high, it was no taller than many of the other buildings in New York. It was a store that sold cut glass, silverware, hand painted china and chandeliers. Its owner knew that people would come to see the elevator and hopefully stay to buy his wares.

Today I am celebrating the life of Elisha Graves Otis who, on this day in 1857, installed the first elevator that was able to safely carry human passengers at 448 Broadway, Manhattan. The E V Haughwout Building didn’t strictly need an elevator. At five storeys high, it was no taller than many of the other buildings in New York. It was a store that sold cut glass, silverware, hand painted china and chandeliers. Its owner knew that people would come to see the elevator and hopefully stay to buy his wares. Luckily, he was rescued by P T Barnum who helped him inject a bit of showmanship into the operation. He paid Otis $100 to bring his contraption to his ‘World’s Fair’ at the Crystal Palace in New York. There, he was suspended high above the crowds on a platform that was held in place by a single rope. Doffing his top hat, he waited for the crowd’s attention then instructed an assistant to cut through the rope with an axe. His audience were terrified when the platform began to plunge floorward, it fell about two feet and then the spring operated brakes came into effect. He announced calmly “All safe, gentleman. All safe.”

Luckily, he was rescued by P T Barnum who helped him inject a bit of showmanship into the operation. He paid Otis $100 to bring his contraption to his ‘World’s Fair’ at the Crystal Palace in New York. There, he was suspended high above the crowds on a platform that was held in place by a single rope. Doffing his top hat, he waited for the crowd’s attention then instructed an assistant to cut through the rope with an axe. His audience were terrified when the platform began to plunge floorward, it fell about two feet and then the spring operated brakes came into effect. He announced calmly “All safe, gentleman. All safe.” Today is the birthday of Nicolas Appert, who was born in 1749 in Châlons-sur-Marne. He worked in Paris variously as a chef, confectioner and distiller. I’m celebrating his birthday today because he is the person who invented a method of storing food in airtight containers that could preserve it for years. He used wide mouthed glass bottles sealed with cork and wax, but his method led to the invention of canned food.

Today is the birthday of Nicolas Appert, who was born in 1749 in Châlons-sur-Marne. He worked in Paris variously as a chef, confectioner and distiller. I’m celebrating his birthday today because he is the person who invented a method of storing food in airtight containers that could preserve it for years. He used wide mouthed glass bottles sealed with cork and wax, but his method led to the invention of canned food.