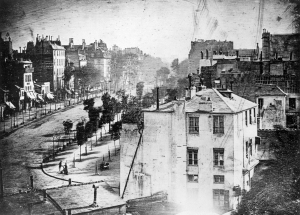

Today I have a milestone in the history of photography. On this day in 1839 the French government gave us the secret of Louis Daguerre’s photographic process. It was their free gift to the whole world (well almost all of it). Daguerre had already been making his images for at least four years (the picture above was taken in 1838) but he was having difficulty raising financial interest. Rather than apply for a French patent he exchanged the secrets of his process for a government pension. I can’t tell why, I lack both the time and the will to look at nineteenth century French patent law.

Today I have a milestone in the history of photography. On this day in 1839 the French government gave us the secret of Louis Daguerre’s photographic process. It was their free gift to the whole world (well almost all of it). Daguerre had already been making his images for at least four years (the picture above was taken in 1838) but he was having difficulty raising financial interest. Rather than apply for a French patent he exchanged the secrets of his process for a government pension. I can’t tell why, I lack both the time and the will to look at nineteenth century French patent law.

Daguerre was an accomplished painter who used a camera obscura to paint enormous canvases which he displayed in his diorama theatre. The camera obscura (which means dark chamber) had been familiar to artists for hundreds of years. It could be used to project a brightly lit image through a lens onto a piece of paper. The image could then be traced but people had long wished it was possible to capture the image they saw without the need for drawing. In the first quarter of the nineteenth century quite a lot of people, Daguerre amongst them, were experimenting with light sensitive chemicals. What was needed though was not only a light sensitive surface but also a way of making it insensitive to further exposure so that the image could be viewed in normal light.

Through the optician who supplied the lenses for his camera obscura, Daguerre met a man named Niépce who was also attempting to fix a photographic image. Niépce was using a bitumen substance to coat a metal plate. The bitumen would harden where it was exposed to the light and the rest could be washed away. These images required an exposure time of at least eight hours, but it did work. The two experimented and exchanged notes for several years and eventually came up with a copper plate that was covered with a thin layer of pure silver which was made light sensitive by coating it with iodine. Niépce died before the method was perfected but his son also received a government pension in recognition of his father’s contribution. Once the plate had been exposed inside the camera it needed to be developed and fixed using fumes of mercury and sodium hyposulfite. If you’re curious, I was, you can watch this little video on YouTube. It seems like an extremely laborious, not to mention dangerous process. Mercury was, after all, the thing that sent hatters mad.

The images produced by the daguerreotype method are really lovely and seem to float above the surface of the plate. The reflective silver surface can make the picture appear as either a positive or a negative image depending on the angle you view it from. The image is extremely delicate and needs to be kept under glass to protect it from damage. Before the introduction of gold chloride into the fixing process, the surface of the daguerreotype was as delicate as the dust on a butterfly’s wing.

Public interest in this new invention quickly became a kind of mania. Within weeks of the French government announcing the details of Daguerre’s method anything remotely related to the making of daguerreotypes was being swept off the shelves as quickly as it appeared. Within months instruction manuals could be found all around the world. It would be the most popular way of making a photographic image for the next twenty years. Millions were produced and many improvements made to the process along the way. It is because of the work of Daguerre and Niépce that we have portraits like the one above, which is the Duke of Wellington and the one at the bottom which is Daguerre himself. Daguerre was not the only contender in the field of photography though. An Englishman called Henry Fox Talbot had come up with a rival method, also in 1839, but that’s another story for another day.

Public interest in this new invention quickly became a kind of mania. Within weeks of the French government announcing the details of Daguerre’s method anything remotely related to the making of daguerreotypes was being swept off the shelves as quickly as it appeared. Within months instruction manuals could be found all around the world. It would be the most popular way of making a photographic image for the next twenty years. Millions were produced and many improvements made to the process along the way. It is because of the work of Daguerre and Niépce that we have portraits like the one above, which is the Duke of Wellington and the one at the bottom which is Daguerre himself. Daguerre was not the only contender in the field of photography though. An Englishman called Henry Fox Talbot had come up with a rival method, also in 1839, but that’s another story for another day.

I did mention at the beginning of this post that Daguerre’s method was available for free to almost the whole world. There was an exception. Five days before the government’s act of extreme generosity Daguerre had taken out a patent which applied to England, Wales, the town of Berwick-upon-Tweed and in all her Majesty’s Colonies and Plantations abroad.